Beauty, Truth, and Love in the Transfiguration of Christ

Today I’m going to focus on what the transfiguration says about the beauty of God, His love, and His Truth.

Have you ever looked around you, perhaps on a mountain, and suddenly been lifted away from everyday perceptions to a profoundly beautiful, even sublime vision? I recall riding a bicycle across a field, my head down, intent on getting to work, when, on looking up, everything flashed with light. It was like someone had turned the lights up several notches. It lasted for a second, but I felt I’d experienced something transcendent.

It was likely not the infinite glory of God but some random nerve firing off in my head. Nonetheless, the world looked truly sublime for an infinitesimally small moment.

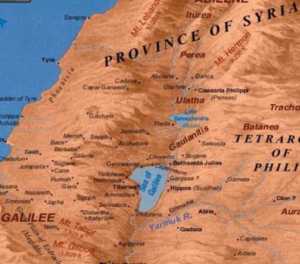

I think my experience might be akin, albeit on a far less true and transcendent scale, to what Peter, James and John experienced on Mount Tabor

… or was it Mount Hermon?

Mt Hermon

Mt Tabor

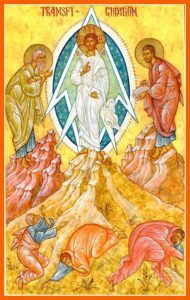

I think the three disciples were given a glimpse of what some commentators call the ‘Uncreated Light’. It is described not as a bodily phenomenon, like when we hit our heads and see stars. Nor is it seen as a mere emanation from God, a light from God. It is the being of God Himself in our world; God is light.

The light is called uncreated light because God was not created; He is who He is. More importantly, God cannot be known in any finite way. Because we can never understand God, we can never see Him fully or completely. God is not an object we can exhaustively reduce to propositions, nor can He be empirically studied objectively. He is perhaps, as some philosophers argue, ‘beyond being’.

He is an uncreated light because rather than unfathomable darkness, he is the unfathomable light that illuminates our world but which we cannot look at directly. Moreover, God, this light, is so beautiful, so sublime that when we look askance at Him, we see Truth. And this transcendent beauty, this ‘Truth’ can provoke nothing if not immense happiness and fulfilment.

Artists have tried to capture the uncreated light, especially at the transfiguration. In Western Christianity, artists such as Raphael have attempted to depict the light more objectively than the deeply symbolic works of Eastern Christianity. However, both traditions still look through a glass darkly.

Modern art also faces a crisis of representation.

Artists have tried to capture the Truth in ways that aren’t too distant from western theologians and scientists, and why shouldn’t they? Art and words evoke things that go well beyond our finite imaginations. Nonetheless, what is True and what is Beauty can never be objectified by mere humans.

Perhaps only in the wild can we come close to seeing God’s face. Though, it is essential to note that we can see the image of God in the face of every person we meet.

I will move from the Truth of Beauty to the Love of God.

In secular ethics, there is a thin stream of thinking about a link between ethics and aesthetics (e.g., Plato to Wittgenstein). That the true and the beautiful are expressions of the good and love.

It is suggested that Satan was the prince of angels, the bearer of light (Isaiah 14:12). God created him to be perfect in wisdom and beauty, a spectacle of flawlessness. But now, there is nothing good in him. He is ugly because he is entirely evil; he has become the frightening darkness that rages across the earth.

Along these lines, Christ’s beauty at the transfiguration points to his overwhelming love. Christ, God, is beautiful because not only does He love, but He is Love. And Love suffuses everything, lights up the world, and keeps the darkness (Satan) from completely enveloping us.

This is why, perhaps, Western and Eastern Orthodox painters have striven to infuse so much light in their paintings of the transfiguration. Look at this Rubens painting, for example. Interestingly, there is almost a greater luminosity to the people around and below Christ than in Christ Himself. Perhaps it’s a distortion in the photo of the painting.

Alternatively, might Rubens have dulled Christ’s face because he cannot paint God as love with enough brilliance? Any attempt to capture Christ’s overwhelming luminance would fail. But Rubens can paint how God’s love illuminates and enlightens those who are in him. Look at the brightness of people’s clothes and especially the luminosity of the demon-possessed boy on the right (Matthew 14:17-20) and the woman in the centre. According to The Vatican Museum, she represents the Church. Light/Love fills them both.

However, we must be cautious here. Love is not easy to define, particularly in words (let alone in painting). To say God is Love begs the question: ‘what is love?’ We can respond with: “Love is God; saying anything more is arrogance”.

Nonetheless, I will pull at my threadbare humility and have a go.

We can detect three linked facets of love in our verses: companionate, compassionate, and attachment love.

Compassionate love, closest to Agape in Greek, covers self-giving, self-emptying, altruistic love, where one prioritises the important needs of the other without concern for one’s interests and moral opinions, and without expecting reciprocity (e.g., deserving poor/tit-for-tat).

God provides the supreme picture of compassionate love. He embodies his being so that He is with us in the flesh, and so we can learn to follow Him. Then He allows himself to be nailed to a cross so that the bondage of sin is broken. Perched, in the middle, at a crucial turning point in Matthew’s gospel, Christ enters the glory of transfiguration, which is a glimpse of the Kingdom. And then, He walks away from the glory back into the crucible of human suffering. He does this, not because He is crazy or immune from suffering Himself, but so that He can save the creatures he compassionately loves and so that we can address the infinity of suffering that rages across the world. Christ swaps the Kingdom for suffering because He loves us with unfailing compassion.

Quite astounding from my all too human perspective!

An omnipotent God allowed Himself to be crucified, killed by the Roman Empire, at the urging of the Jewish leaders, and in front of His disciples. But then He rose from the dead, defeating the earthly powers, thereby showing us that although we may also be called to die for the suffering Other, we will eventually join Him in the New Heaven and Earth.

As an aside, let me stress we should not infer that compassionate love is some reckless dive into the melee of suffering. It takes discernment and planning to act with compassionate love. The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit knew what they were doing; they did not take a blind leap. In the ugly words of managerial speak, God strategises.

God, at the transfiguration, also enacts companionate love, which is a deep friendship or familial love directed to significant people in one’s life, such as family and friends.

Most powerfully, the Father expresses deep companionate love when He says:

“This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased; listen to him.” (Matthew 17:5).

‘Beloved’ here, I suggest, implies a deep relationship with the other. Expressing ‘compassionate’ love does not demand the ‘other’ love us; they need not be our beloved. They may hate us. But ‘companionate’ love points to deep mutual and emotional bonds.

One must admit, though, sometimes parents continue to love their children even though their sons or daughters have rejected them. I guess the same can be said for God who continues to love humans who have denied him.

However, this may be best understood as an example of where love must become more compassionate than companionate. Some of our brothers and sisters, fathers and mothers, sons and daughters both beyond and within the church, may dislike us so much that companionate bonds are broken, but we can still have compassionate love for them. This is, of course, what God does easily; He is Love. Loving those who hate or reject us is rarely easy, but we are called to try, as Jesus points out in His sermon on the mount.

Adding to all this, I suggest that God, the Son, exhibits a companionate love for the three disciples at the transfiguration. They are so close to him and He to them that they are like a very caring family. Christ deeply loves His beloved disciples, so He shares His divinity with them. We can also share this with Christ – we can have a deep relationship with him; we are His beloved children.

Perhaps this is what Rubens points to with the purported image of the church as a beautiful woman – we are the church; we are the beloved.

Focussing now on Peter, some have argued that he stumbled into a moment of foolishness or self-interest when he said, “Lord, it is good that we are here. If you wish, I will make three tents …, one for you and one for Moses and one for Elijah.” (Matthew 17:4). But I suggest that he was also expressing what modern psychologists call ‘attachment love’. That is, an emotional bond we place in someone who offers security, comfort, or meaning, such as a parent, caregiver, or in Peter’s case, Jesus. He is a disciple of Christ, which implies not just intellectual attachment but also emotional attachment.

Saying “it is good here” and suggesting tents might imply Matthew would like all of them to take up residence on a mountaintop far away from the threats and exhausting journey they have all been on. I certainly think I would want more than a short heavy sleep (Luke 9:32), especially if it’s Mount Hebron I had just climbed. Others have been a bit more forgiving, arguing that he said what he said to “secure in place, if not tie down and domesticate, the wild spirit of God‘s kingdom”. (Dörnyei, 2022)

Also, it is true, as Luke remarks, “not knowing what he said” (Luke 9:33) Peter, still befuddled by sleep, blurted out the first thing that came into his mouth. I’ve certainly done that, and sometimes even if I haven’t just been asleep!

However, whilst these kinds of frailties likely played a part (Peter is still on his journey as a disciple) I want to suggest that he is also showing some companionate love and maybe even a little compassionate love – he didn’t ask for his tent, after all.

But, more importantly, I think Peter is expressing attachment love.

Peter has an emotional attachment to Jesus partly because Jesus offers him security, comfort, meaning, instruction, and counsel. Jesus is for Peter, what our mothers, fathers and educators were for us in our childhood. Of course, at some point, parents must encourage their children to leave home, and educators must eventually send students into the world. Perhaps, this is one more reason Christ left us to be with the Father. We may have the Spirit in His stead, but we must still stand on two feet and learn through experience.

Given this, why then wouldn’t we expect Peter to try to keep Christ unharmed and embodied? Do not most young children cry when their parents leave them alone in their bedroom? It’s only in their teens that many hide away in their bedrooms and get angry when parents want to enter their sanctuary.

And don’t children sometimes fear the death of their parents, just as Peter did when he tried to rebuke Jesus, saying, “Far be it from you, Lord! This shall never happen to you.” (Matthew 16:22). Jesus replied (in addition to get behind me Satan) “(f)or you are not setting your mind on the things of God, but on the things of man” (Matthew 16:23).

So, what does all this mean for us?

At the most esoteric level, Jesus Christ is Beauty, Truth and Love and, thereby, the foundation upon which we can build a good and hope-filled life. They are Archimedean points for discernment, pointing us in the direction we should walk towards our mount of transfiguration.

Thus, when we see a painting, the natural world or any view, the profound beauty of which takes our breath away, we also see God and Love and thus a glimpse of our goal: the Uncreated Light of God and His Kingdom.

Some may say, “in this fallen world, beauty is so subjective; it is just in the eye of the beholder”. I would say: yes, our brokenness and Satan do indeed distort Beauty, Truth, and Love – fracture them into a thousand shards. But God has written the law on our hearts, which is, I suggest, not just the law of Love but also Beauty and Truth. And I believe our appreciation and understanding of Love, Beauty and Truth will grow as we grow in Christ through prayer, worship, Bible study (especially together) and the many other spiritual practices we can learn.

Finally, this law (in sum loving the lord and others, including our enemies) suggests, I think, that we should also look for Truth, Beauty, and Love in all God’s creatures, and especially in the faces of all fellow humans. This may sometimes be very hard to do, but let us try and let us at least look beyond surface appearance as well as individual and cultural differences. Amen.